Reasoning About Privacy in Smart Contracts

(originally posted here as part of the PRIViLEDGE project, EU 2020 HORIZON; however that website seems to have died)

Smart contracts have become a standard way to implement complex online interaction patterns involving the exchange of both cryptographic currency and data on blockchain in a unified and generalised manner. This approach was popularised by Ethereum, and examples include ERC20 token contracts, decentralised exchange contracts (Idex, EtherDelta), and even contract-based games, like CryptoKitties. Smart contracts allow both developers and regular users to express complex behavioural requirements and patterns using a high-level programming language. At the same time, the public nature of most popular smart contract systems restricts the expressivity of contracts. Public fields of the contract are visible to everyone, and transactions reveal a lot of private data – which address triggered the contract change, and what this execution was like. Many privacy-preserving communication patterns that need this information to be private and accessible to only specific parties run into resource or design complexity limits, even though it is theoretically possible to implement them. Moreover, the security proofs for these types of systems are cumbersome because of additional non-standard and non-unified layers of abstractions introduced by implementing the privacy-preserving logic on top of the public smart contract functionality instead of designing smart contracts environments with privacy support in mind.

In this blog post we will look at the two proposals for private smart contract systems, namely Zkay [1] and Kachina [2], both of which provide a way to express different privacy properties in smart contracts, and to reason about them. While Zkay serves as an illustrative example of a practical smart contract framework, showing the end user’s or programmer’s perspective, Kachina offers a more theoretical take on what privacy is, allowing for detailed security analysis of the functionalities involved in the smart contract.

Zkay system consists of the language, more precisely an extension of the Solidity language used in Ethereum, and a compiler that transforms the smart contract code into two independent pieces of code – the Solidity contract that can be run, for example, on the Ethereum blockchain, and a circuit description of the code that is supposed to be run inside a zk-SNARK. The zkay language is different from its base Solidity language in having fine-grained privacy annotations that specify the ownership of the internal contract variables – if T is a type of variable, then T@A is a T data structure that belongs to the address A. These privacy annotations allow limiting the access of the concrete script variable to the concrete single user’s address, so that the variable can only be read by the owner of that address. Another important language feature is careful handling of statements that reclassify the secret information – whenever one wants to publish a secret value, or give it away to another party, a call to the reveal function allows it to do that. In this way, semantics of the language separates private computations from the public ones, and forces the contract author to explicitly declare this boundary.

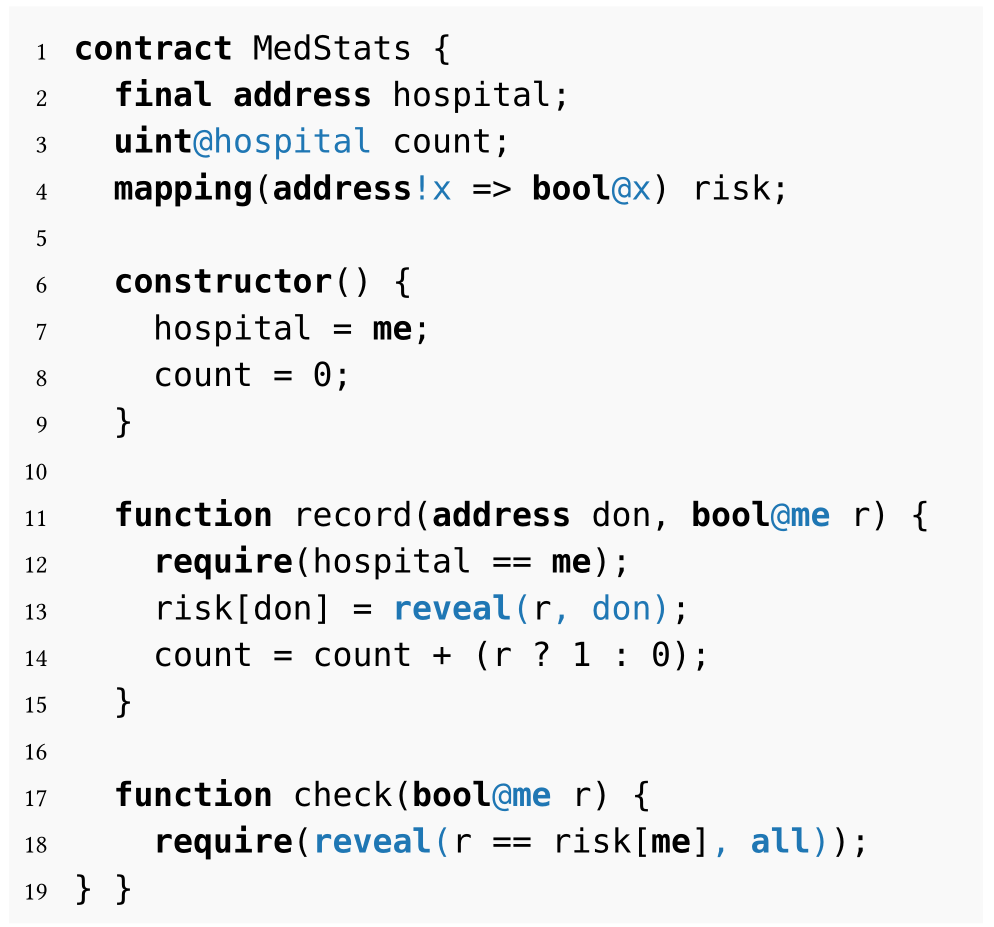

The main example in the paper, presented on Figure 1, presents a smart contract MedStats that emulates a simplistic medical database. This contract stores a variable mapping each user to a boolean value that indicates whether this user is in a risk group or not (called risk), and a global private counter of all the users in the risk group. The entity hospital can then assign these values and increase a private counter (that is not visible to anyone else), and users can read their own risk assignment from their own private element of the mapping risk (and again, nobody else can read from it). The smart contract guarantees that the counter is consistent with the risk information given to users.

In this example, we clearly see that privacy is ensured in a way that is understandable for programmers – adding an additional language feature which induces extra privacy semantics. This kind of semantics could be (and is) achieved within more powerful languages by using strict types; one good analogy is private/public object fields, or state and reader monads in functional languages. These language features restrict the behaviour that we want to avoid, namely revealing secret information to other parties, by performing type-checking. Under the hood, ZKay extracts the private parts of the contract into arithmetic circuits, that update the encrypted values, corresponding to the private variables. And the correctness of transition from one private state (with one set of variables) into another is guaranteed by the zk-SNARK which is parameterized by this extracted circuit. Now how privacy is achieved makes perfect sense – we update certain encrypted values in zero-knowledge, but does it allow us to express all the private contracts we would like to work with? Is there a simple way to concisely present the exact places we might leak information from? For instance, if we update a certain encrypted value, the very fact it was updated is publicly visible (because the ciphertext changes whenever the underlying plaintext changes), so this absence of unlinkability seemingly prevents us from implementing zcash-like transactions using just the tools provided.

Kachina [2] approaches these issues from the opposite direction. Instead of defining a programming language extension it provides a most general abstraction for public and private state separation, together with a framework in which contracts can be proven secure. At the base of Kachina lies the Universal Composability (UC) framework [3] – a set of formal specification and proof techniques that allow proving cryptographic protocols secure. Kachina builds on UC, and suggests the following contract design flow.

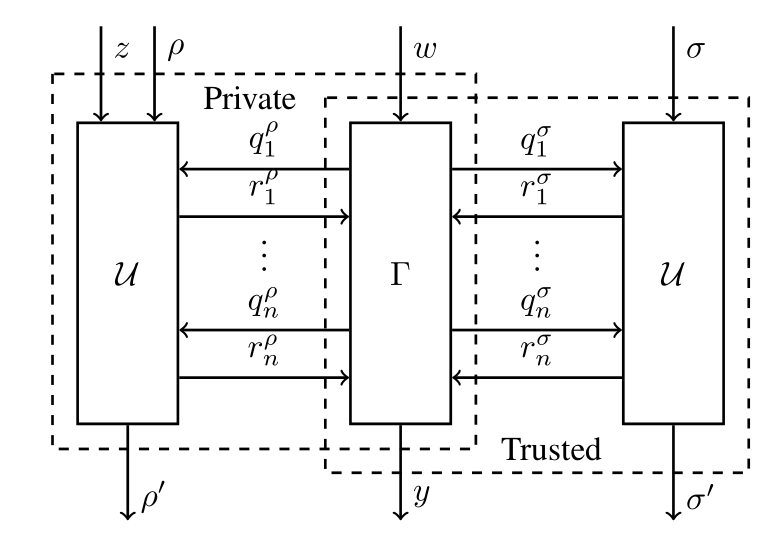

First, we need to formally specify, in the UC pseudocode language, the contract transition function \(\Gamma(w)\) – the core of the interaction of users and the contract. This function, although may look quite similar to any other contract one may come across, has a distinctive restriction – it must be written in such a way that interactions with the public state of the contract and a set of private states (one per user) are abstracted as communication with separate programs, called public or private state oracles respectively. This forces us to separate publicly accessible information, such as public contract variables, from the private states of users, which are generally stored on the user side, and may include secret keys, nonces, etc – whatever is needed to act as a contract party. Moreover, the transition function itself doesn’t maintain any state, since it is all delegated to the oracles. This state-oracles approach itself may sound reasonably familiar to programmers, as it is ubiquitous in software engineering (imagine oracles being internal objects of the functionality object, with call access to them only), but the difficult problems solved by Kachina lie more in the precise definitions and abstractions that allow us to later reason about this transition function. Figure 2 show the transition function \(\Gamma\) transforming smart contract input \(w\) (which can be thought of as a query, or RPC with the arguments), to the output y, while communicating with a public oracle at the right side, transforming public state \(\sigma\) to new \(\sigma'\), and correspondingly a set of private oracles each changing private state \(\rho\) to \(\rho'\).

The transition function is itself a minimal piece of logic that describes the behaviour of the contract. It answers the main question “given a certain request to the contract, how will our public and private states change?”. But to proceed with the proof and to reason about system security guarantees, we will define two more objects – an ideal behaviour function \(\Delta\) and a leakage function \(\Lambda\). The first one expresses a high-level intuition about the behaviour of \(\Gamma\) – as if there were no concrete cryptographic objects in the contract, and it was allowed only to emulate the behaviour of the contract, allowing for adversarial input. The leakage function maps every possible input to the contract to the leakage that this contract does provide. After defining these two objects that precisely specify our expectation about functionality that we provide, possible adversarial interference, and a leakage, we can proceed with the security proof in the UC manner. Kachina then guarantees the soundness of the system – that is, it won’t be possible to prove the system secure if our leakage expectations \(\Lambda\) are strictly weaker that the real leakage, or if our modeled behaviour and possible attacks in \(\Delta\) are less general than ones allowed by the transition function defined earlier. In other words, security is guaranteed by reducing the functional and leakage related claims to a small readable piece of pseudocode (that we can agree or disagree with), and then proving the real contract correspondence to it.

The real contract that can be put on the blockchain modifies our contract transition function \(\Gamma\), transforming our abstract communication-with-oracles pattern into zero-knowledge proofs of the fact this communication (together with its private parts) corresponds to the contracts’ code. Many more parts of Kachina help us to understand and write the contract, for instance it provides a way to formalise public and private state consistency, allow for proper transaction reordering, and so on.

Thus, Kachina serves as a general framework, in which the security properties can be concisely expressed, and the correspondence of the concrete smart contract system can be proven secure with respect to these properties. Being a theoretical work, Kachina does not provide a language or a compiler, but relies itself on the UC language. At the same time, its expressive power is quite high – it easily captures zcash-like private payments (which is the main example in the paper’s body), and the zkay privacy abstraction, with its encrypted value transitions, can also be quite straightforwardly expressed in Kachina, putting encrypted values into the public state, while having secret keys in the private ones.

Our research focuses on bringing these ideas together – is it possible to extend Zkay language annotations even further? What would be the best smart contract language to provide a seamless integration with state-oracle abstraction – either by using the interface to define them directly, or transforming other approaches, as, for example, privacy types access, into the code that will fit the state oracle abstraction criteria? Parts of these questions are to be resolved by the ZK toolkit, which is currently under research and development.

References

[1] Steffen, Samuel, et al. “zkay: Specifying and enforcing data privacy in smart contracts.” Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2019.

[2] Kerber, Thomas, Aggelos Kiayias, and Markulf Kohlweiss. “Kachina–Foundations of Private Smart Contracts.” https://drwx.org/papers/kachina.pdf

[3] Canetti, Ran. “Universally composable security: A new paradigm for cryptographic protocols.” Proceedings 42nd IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. IEEE, 2001.